Azimjon Askarov, an investigative reporter and human rights defender, had ended careers and embarrassed officials time and again with his reporting on law enforcement abuses in southern Kyrgyzstan. When ethnic unrest broke out in June 2010, authorities struck back with a vengeance. A CPJ special report by Muzaffar Suleymanov

Published June 12, 2012

NEW YORK

Ethnically motivated beatings, arsons, and killings were sweeping through southern Kyrgyzstan, and Azimjon Askarov was exhausted. It was early on June 13, 2010, and Askarov, a prominent reporter and human rights defender, had been up all night documenting the unrest that pitted ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks against one another, a conflagration that ignited three days before in Osh and was now racing through his village of Bazar-Korgon.

At 5 a.m., unable to stay awake, Askarov asked a companion to drive him home. About four hours later, Askarov recounts today in an interview for CPJ, his wife awakened him with news: A police officer had just been killed. Askarov roused himself, grabbed his camera, and headed out, going first to his office and then to the scene of the killing on the nearby Bishkek-to-Osh highway, a mountainous four-lane thoroughfare where hundreds of ethnic Uzbeks had massed in an effort to block what they perceived to be Kyrgyz efforts to move aggressors and weapons into the region.

More on this issue

• CPJ’s recommendations

Case documents

• Verdict

• Appeal

• Medical exam

In print

• Download the pdf

In other languages

• Русский

The situation was tense as he arrived, Askarov recalls, as police were firing into the crowd and a civilian, bleeding, dropped to the ground in front of him. In all, three civilians were killed in the village that day along with the officer, the human rights group Kylym Shamy said. By the time the violence subsided in Bazar-Korgon on June 15, at least 19 were dead, more than 130 were injured, and more than 400 buildings had been torched, according to accounts from the government, news outlets, and human rights groups. Askarov was among those keeping a close tally, visiting the morgue to identify bodies, interviewing local residents and officials, keeping a diary with his extensive notes, shooting videos, and taking photographs.

But two days after the confrontation on the highway, Askarov was himself in police custody, where he would endure prolonged brutality during which officers “beat me like a soccer ball.” Today, two years later, Askarov, a 61-year-old Bazar-Korgon native of Uzbek descent, is serving a life prison term on charges that he was complicit in the officer’s murder and had committed a series of other anti-state crimes. The conviction has been challenged by the government’s own ombudsman’s office, and Askarov’s lawyers are now preparing a complaint to be filed with the U.N. Human Rights Committee.

A reporter who exposed abuses

The case against Askarov boils down to three broad allegations: that he incited the crowd gathered on the highway to kill Myktybek Sulaimanov, a police officer, sometime after 8 a.m. on June 13, 2010; that, a day earlier, he fired up another crowd to take a local mayor hostage, a crime that did not actually take place; and that he possessed 10 bullets, which were found in his home during a police raid marked by irregularities.

By September 2010, Askarov had been convicted on the thinnest of evidence, the testimony of self-interested police and public officials who claimed he made remarks to incite crowds to violence. Yet Askarov was not observed participating in any act of violence and, aside from the disputed bullets, was not linked to any crime by any other evidence. His trial was conducted in an atmosphere of intense intimidation of the defense—Askarov and his lawyer were assaulted during the proceedings—and a general climate of fear among the Uzbek population, all of which served to deter would-be defense witnesses. People who could have provided exculpatory testimony—including Askarov’s wife and neighbors, whose accounts contradicted those of police—were ignored by authorities and too frightened to testify.

Police and prosecutors had plenty of reason to target Askarov. During years of investigative reporting on law enforcement corruption and human rights abuses in southern Kyrgyzstan, Askarov had ended careers and embarrassed local officials time and again. His reporting on the June 2010 ethnic unrest, which included photos and videos, provided yet another reason for authorities to fear him.

“Certainly Bazar-Korgon police and prosecutors benefited from my imprisonment—they’re the most criminal among Kyrgyzstan’s law enforcement agencies,” Askarov said from Penal Colony 47 outside Bishkek in comments recorded for CPJ by his lawyer, Yevgeniya Krapivina. “I always obstructed their corrupt work. … They hated me.”

Askarov was an artist by training, specializing in landscape painting, but he was far better known for his work in human rights and investigative journalism. He founded the human rights group, Vozdukh (Air), and in articles published in his group’s bulletin, Pravo Dlya Vsekh (Justice for All), and on the regional news websites Golos Svobody (Voice of Freedom) and Ferghana News, he exposed abuses and got results.

In 2003, Askarov’s reporting led to the release of a local woman who was repeatedly raped by police and male detainees during her seven-month-long pretrial detention. More muckraking reports followed. In 2004, for example, Askarov investigated the case of a local man who died after being beaten in police custody, local journalists reported. Most notably, in 2007, he derailed the prosecution of a local couple charged in the murder of a woman named Mairam Zairova. Askarov tracked down Zairova in Uzbekistan, where she was very much alive, and produced her in court. With the corpse misidentified, the prosecution’s theory collapsed and the couple was cleared. The regional prosecutor was sacked because of the botched case, another in a series of disciplinary actions and dismissals of police officials and prosecutors stemming directly from Askarov’s investigative reporting, Daniil Kislov, editor of Ferghana News, told CPJ.

“I believe it was his work on Zairova’s case that prompted the police to seek revenge,” said Nurbek Toktakunov, another of Askarov’s lawyers. And spring-summer 2010 was, according to two independent investigations, a time when law enforcement standards had broken down in southern Kyrgyzstan. The investigations, conducted by the New York-based Human Rights Watch and a commission sanctioned by the United Nations and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, each found a pattern of prejudicial law enforcement in the aftermath of the unrest, with ethnic Uzbeks disproportionately targeted for arrest and imprisonment.

A pattern of bias

Throughout southern Kyrgyzstan, the June 2010 ethnic unrest claimed the lives of at least 470 people and displaced thousands of others. Although a June 10 ethnic brawl in an Osh casino marked the beginning of the violence, tensions had been high since the April 2010 ouster of President Kurmanbek Bakiyev. Jockeying for power in the ensuing vacuum, Kyrgyz politicians had courted the support of ethnic Uzbeks, a traditionally apolitical but economically thriving bloc concentrated in the south. Ethnic Kyrgyz, who hold most governmental and law enforcement positions in the south, as they do elsewhere in the country, grew fearful at what they perceived to be the Uzbeks’ newly elevated political position. In particular, Kyrgyz residents perceived Uzbek-organized rallies against Bakiyev as calls for southern autonomy.

Ethnic Uzbeks bore a heavier toll during the June violence, both as victims of violence and detainees held on allegations of committing the violence, Human Rights Watch reported. “Ethnic Uzbeks constituted the large majority of victims of the June violence, sustaining most of the casualties and destroyed homes, but most detainees and defendants—almost 85 percent—were also ethnic Uzbek,” Human Rights Watch found. “Of 124 people detained on murder charges, 115 were Uzbek. Taken together with statements from victims describing law enforcement personnel’s use of ethnic slurs and focus on the ethnicity of alleged perpetrators and victims during detention, these statistics raise serious questions about ethnic bias in the investigation and prosecution of crimes during the June violence.”

No other crime committed in Bazar-Korgon during the June 10-15 unrest was successfully prosecuted, according to accounts from Toktakunov and local human rights defenders.

CPJ’s research has found that the once-vibrant Uzbek-language media in southern Kyrgyzstan was virtually erased in the aftermath of the violence. The morning after clashes erupted in Osh, the regional government ordered Osh TV and Mezon TV, independent stations with Uzbek owners, to cease their broadcasts. Authorities alleged the stations had incited violence; CPJ’s review found they had covered rallies by ethnic Uzbeks but had not orchestrated calls for violence. Both stations suffered heavy damage from unidentified vandals, and Mezon TV never returned to the air. While Osh TV did resume broadcasting, it was ultimately transferred to ethnic Kyrgyz ownership after it faced a series of official raids, seizures, and detentions.

Despite its declared commitment to press freedom and the rule of law, the national government has effectively turned its back on repression in the south and the reported abuses in the Askarov prosecution. Former President Roza Otunbayeva, who said publicly in May 2011 that Kyrgyzstan had no persecuted reporters, did not respond during her tenure to CPJ letters seeking intervention. Her successor, Almazbek Atambayev, has not responded to renewed calls for Askarov’s release. Kyrgyzstan’s Prosecutor General Aida Salyanova, the country’s top law enforcement official, did not respond to written questions submitted by CPJ about the case, among them whether her office has examined reports of police brutality against Askarov.

‘Blame yourself’

Askarov would be arrested on June 15, 2010. He had spent the two days since the highway confrontation visiting the local hospital, scouring the streets of Bazar-Korgon, interviewing the wounded, and sharing information with Moscow- and Bishkek-based journalists and human rights defenders, including those with the OSCE’s Kyrgyzstan office. Askarov said his dispatches included details on the movement of arms in the region, and police abuses that included at least two shootings that he had witnessed. His work was commonly known. Askarov recalls a local judge, Daniyar Bagishev, encountering him on the street on June 15 and warning him to stop gathering information on the crisis. “You are venal and sell these materials for U.S. dollars. But this information is a state secret and nobody should learn about it,” Askarov remembers the judge saying. Contacted by CPJ, Bagishev declined to comment.

A half-hour later, a police cruiser arrived at Askarov’s house: “You need to come with us,” he was told.

Before leaving with police, Askarov said, he managed to slip his digital camera, with its stored images, into a folder he gave to an acquaintance. Fearing what might happen to Askarov, local human rights defenders then scrambled to hide his other reporting files and move the journalist’s wife and other family members to safety. His family ultimately left the region.

Once at the local precinct—the same station where Sulaimanov, the slain police officer, had worked—officials asked for Askarov’s help in building criminal cases against leaders of the Uzbek community. “Tell us who of them had guns,” officers demanded, and he refused. They asked him for his camera and reporting materials, and he lied about their location. Officials soon took Askarov into custody. “Blame yourself,” Askarov recalls being told. Thus began an ordeal in which police officers repeatedly beat Askarov and told him they would rape his wife and daughter if he refused to hand over his reporting materials. His brother, who came looking for him, was himself beaten badly, Askarov said.

For Askarov, the beatings would continue for the next three days, during which he was denied access to a lawyer. The journalist told CPJ that officers beat him with a gun, baton, and a water-filled plastic bottle. Once, he recalled, he was beaten so badly that he fell unconscious. “After I stood up, they made me sing the Kyrgyz anthem even though I was barely alive. Next, they took me to an investigator’s room, where a police agent named Nurbek hit me with his gun handle in the head. My head was bleeding like a slaughtered chicken,” Askarov told CPJ.

After Toktakunov, the defense lawyer, was finally allowed to see his client, he took a statement in which Askarov said he had been beaten by police and needed medical treatment. But the journalist was soon coerced into recanting. “Police threatened to strangle me with a pillow at night if I did not withdraw my request for a medical exam,” Askarov told CPJ. “I had no other choice.” Questioned about the abuse by a CPJ representative at a May 2011 meeting in New York, Kyrgyzstan diplomatic officials and presidential aides asserted that Askavov had been beaten by a cellmate. Police would hold Askarov in the local precinct, among Sulaimanov’s inflamed colleagues, for more than a month, contrary to a law that requires detainees to be moved to a Ministry of Justice facility within 10 days.

According to Human Rights Watch and Askarov’s own account, the beatings continued even as trial proceedings began in September 2010. In one instance, Askarov told CPJ, “three policemen beat me like a soccer ball outside the courtroom, saying that I was too intelligent and was not letting them prosecute me.” Toktakunov was himself assaulted—in the presence of court officials—by relatives of the slain police officer. Human Rights Watch said the judge called for order in the courtroom but “did not warn or discipline any of the abusive spectators.”

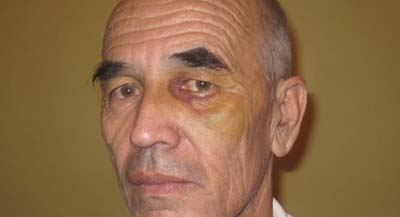

Askarov has suffered “severe and lasting” effects from the brutality, according to Sondra S. Crosby, a physician whose clinical practice at Boston University School of Medicine focuses on torture. Crosby, hired by the Open Society Justice Initiative, which is helping prepare Askarov’s U.N. complaint, examined Askarov in jail in December 2011, more than a year after most of the abuse occurred. She found that he “appears to have suffered severe and lasting physical injuries as a result of his arrest and incarceration. His description of acute symptoms, as well as chronic physical and psychological symptoms, his physical examination, and his psychological evaluation, are all highly consistent with his allegations of trauma.”

Thin and disputed evidence

The trial would bring no relief for Askarov. As proceedings were getting under way, a regional prosecutor told the journalist he should forget about the due process he often cited in his news reports, Askarov told CPJ. “We will prosecute you according to other laws,” the prosecutor said.

Askarov was tried in Bazar-Korgon District Court alongside seven co-defendants. All faced charges of inciting disorder; four were directly charged with Sulaimanov’s murder. All would be found guilty, including Askarov, who was convicted of complicity to murder, attempt to take hostage, incitement to ethnic hatred, participation in mass disorder, and possession of ammunition. Although some co-defendants had made self-incriminating statements, none implicated Askarov in any wrongdoing.

The murder-complicity case against Askarov was based on testimony from Sulaimanov’s fellow officers who were dispatched to clear the highway of protesters at about 8 a.m. on June 13, 2010. Confronted by an angry crowd that was several hundred strong, the officers quickly retreated but Sulaimanov was not among them. Assailants stabbed him several times and burned his body with a Molotov cocktail, the verdict said. No police officer testified as having witnessed the killing, which was believed to have occurred at about 8:30 a.m.

But seven officers, including the Bazar-Korgon police chief, told the court they saw Askarov in the crowd beforehand calling on the protesters to “kidnap the police chief and kill the others.” Six other police officers testified against the co-defendants, but they either did not place Askarov at the scene or told the court that another man had made the calls to violence, the verdict said.

By his own account, Askarov said he showed up at the highway well after the crime was committed. An investigation commissioned by the government’s ombudsman’s office, which oversees human rights issues, concluded that Askarov was not at the scene prior to the murder and played no role in the officer’s killing. The ombudsman’s office said it reached its conclusion after interviewing witnesses and local officials, and reviewing investigative reports.

The attempted hostage case was built on the accusation of the local mayor, who said the alleged crime took place on June 12, 2010, near the Uzbekistan border, as the official was trying to stop ethnic Uzbek residents of Bazar-Korgon from seeking refuge in the neighboring country. Mayor Kubatbek Artykov alleged that Askarov called on “unidentified” people in the crowd to take him hostage, an account that only two mayoral aides could corroborate. No actual hostage-taking attempt took place, according to the verdict. Askarov confirmed that he talked to the mayor that day, but only to ask if the official could guarantee the safety of the Uzbek villagers. He said the mayor refused.

The defense also disputes the reported search of Askarov’s home, during which investigators claimed to have found 10 bullets for a Makarov pistol. Investigators failed to produce in court any witnesses to the seizure, a step required under Kyrgyz law, and they failed to seal the bullets as evidence, which is also required. No pistol was found. “They made up that police report to lock him up longer,” Toktakunov told CPJ.

Atmosphere of hostility, intimidation

The defense has argued that investigators failed to take statements from any witness who would have spoken on Askarov’s behalf, including neighbors who witnessed him at home during the time the police officer was killed, and a mullah who witnessed the journalist’s encounter with the mayor. The overall climate of fear and intimidation, coupled with authorities’ inaction in response to attacks against the defendants and their lawyers, made it impossible for defense witnesses to testify on their own initiative, Toktakunov told CPJ. “Authorities refused to guarantee any protection for the witnesses, and I could not risk bringing anyone to court,” he said. One potential character witness considered testifying despite the risk, he said, but dropped out after receiving threats against her family.

In an appeal to the Kyrgyzstan Supreme Court, Toktakunov cited a “lack of impartiality” at trial. He noted that his request for a change in venue for the trial was rebuffed despite the widespread ethnic hostilities in southern Kyrgyzstan at the time. Judge Nurgazy Alimkulov failed to inquire about the evident bruising on Askarov’s face, and did not discipline those in the courtroom who attacked and threatened the defendants, Toktakunov noted. The atmosphere prevented Askarov from getting a fair trial, he wrote. “In conditions of fierce moral and psychological pressure, defense lawyers in the case had to fulfill their duties with great caution, at times declining to use certain resources. For example, all of the defendants’ lawyers decided not to bring defense witnesses to court because the court authorities could not guarantee their safety.”

Kyrgyzstan’s Supreme Court rejected Askarov’s appeal following a hearing that the defendant was not allowed to attend.

Domestic appeals exhausted, defense lawyers are preparing a complaint to be filed with the U.N. Human Rights Committee, arguing that Kyrgyzstan violated Askarov’s rights under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights—in particular, his right to liberty and security, his right to a fair trial, and his right not to be subjected to torture. Among the complaint’s central points: Police tortured Askarov in custody; authorities failed to investigate the abuse or grant Askarov independent medical treatment; authorities denied Askarov access to an attorney and failed to provide him sufficient time to prepare a defense. The complaint is expected to ask the U.N. body to recognize the injustices Askarov suffered, call for his immediate release, and seek an investigation into the abuse that would lead to the punishment of those responsible. In addition, the lawyers will ask the Human Rights Committee to demand that Kyrgyzstan introduce systemic safeguards to prevent similar violations from happening in the future.

Askarov and his lawyers also hope that Kyrgyz authorities will, on their own, revisit the case based on statements from numerous witnesses who have agreed to testify if their safety can be ensured. In statements collected by defense lawyers and made available to CPJ, at least five people said they saw the journalist at home at the time of the police officer’s killing. Askarov’s lawyers said they are collecting statements from another two dozen witnesses who dispute the other allegations.

“He is imprisoned,” one neighbor’s statement said, “for nothing.”

Muzaffar Suleymanov is the research associate for CPJ’s Europe and Central Asia program. He was a contributor to CPJ’s 2009 report, “Anatomy of Injustice,” an examination of unsolved journalist murders in Russia.

CPJ’s recommendations

To the president of Kyrgyzstan:

- Take all legal steps necessary to ensure that Azimjon Askarov is released and his conviction overturned.

- Publicly call for a timely, thorough, and professional investigation into attacks against the press.

- Publicly call for national law enforcement agencies, security services, and prosecutors to comply strictly with national and international laws on press freedom, human rights, and prevention of torture and other forms of cruel treatment against detainees.

- Carry out a review of interior ministry officers and prosecutors in conjunction with the Kyrgyz ombudsman’s office and human rights activists, and make the findings public.

- End persecution of the independent, Uzbek-language press.

To the Kyrgyzstan’s Ministry of Justice, General Prosecutor’s office:

- Launch an open and thorough investigation into the torture of Askarov, his brother, and co-defendants in the case, and bring all those responsible to justice; conduct the probe in compliance with the Istanbul Protocol’s guidelines on Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.

- Ensure that Askarov’s co-defendants are given the opportunity to appeal unjust verdicts and that the process is transparent and conforms to Kyrgyz law and international standards.

- Ensure that Uzbek-language media representatives are given the opportunity to appeal unjust verdicts and the forced sale of their outlets, and that the process is transparent and conforms to Kyrgyz law and international standards.

To the United Nations Human Rights Committee:

- Admit and review Askarov’s case.

- Press Kyrgyz authorities to unconditionally fulfill national and international commitments to press freedom and human rights.

To the U.S. government, European Union, and OSCE:

- Publicly call on the Kyrgyz government to release Askarov immediately and unconditionally.

- Encourage Kyrgyz authorities to fulfill their domestic and international commitments to human rights and free expression as a basis for mutual political dialogue.

To donor agencies, including USAID, World Bank, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development:

- Insist on compliance with international standards for press freedom and human rights as the basis for continued economic cooperation with the Kyrgyz government.